"The destruction of Mecca" (The Economist, 2017), a.k.a. "the cash machine". The Mammon mammoth hotel looks like

a cross between London's Big Ben and New York's Empire State Building. By their fruits you shall know them...

A friend asked what Salafism was. There is a lot of confusion on this

subject, and rightly so. Thinking about the matter, I came up with two

answers, one short and one long. I share some of my thoughts below, in

the hopes that others might benefit as well.

(I have to admit that, when I began to do the research for this

article, I had no idea what I was going to find out about Wahhabism. I

was unaware that the situation was this grave. Some of the info I

uncovered had become available as recently as 2020, when this article

was written. In other words, the conclusions I reached here were forced

upon me.

In what follows, I discard diacritical marks, and the usual “al-”

prefix that precedes Arabic proper names. Dates are given as CE/AD. I

also shorten the cumbersome “Ibn Abdul Wahhab” to “Abdul Wahhab”,

although I am aware that the former is the right way to name him.)

The Short Version

There are some words in languages that have double or even triple

meanings. These can lead to confusion, and so need to be clarified. One

such word is church: it can mean a physical building of worship, a community of Christians, or a quasi-bureaucratic institution.

We have such words in Arabic as well. One example is sunna,

which means the Way of the Prophet (his words and deeds), but also

circumcision. The context is expected to specify which is meant. Another

such word is sharia. One meaning is the Divine Law, the set of

obligations that every Moslem is expected to follow: perform the

Prayer, abstain from alcohol, and so on. The other meaning is codified

Islamic Law imposed on a community of believers.

And so, too, is the word salafi.

The original meaning refers to the first three generations that bore

witness to the Prophet: his Companions, their Successors, and the

Successors of the Successors. These are called the Pious Ancestors (salaf al-salihîn), whence the term salafi

(follower of the Righteous Forebears) derives. According to the late

Harald Motzki, the first generation lived until approximately 690, the

second until 750, and the third until 810 CE. [1] However, some people extend the salafi period to three centuries after the Prophet’s passing (632 CE).

All Moslems hold the piety of these generations in the highest regard,

for it is through them that the religion has come down to us. In

discussing the various paths within Islam, Master Ahmet Kayhan said,

“Now the best is the Salafiyya. That is, the Sunnis, not to stray from the Koran and the Way of the Prophet. This is the path of [true] Islam.”

Now this, namely salafi as early believers living in a historical period and place, has to be sharply distinguished from salafism

as a philosophical, even ideological, movement that began in the

18th-19th centuries. (Olivier Roy used to refer to salafism as

neo-fundamentalism. Others have called it simply “fundamentalism”.)

To tell the two apart, I will refer to the first as salafis and the second as salafists.

The latter is not a single category, but covers a spectrum of

individuals and approaches. Two main tendencies can be discerned: the

modernist project of the 19th-century reformers, and the Wahhabis of

Saudi Arabia. The Islamists (who advocate a politicized Islam) are also

frequently included.

A prominent place in salafism is occupied by Wahhabism. Starting from

the 1920s, when the term salafism began to be used, Wahhabis have

presented themselves as salafis (by the 1929 order of King Saud

himself), a more value-neutral term that does not carry the historical

baggage of Wahhabism. By their own definition, every Wahhabi is a

salafi, but not every salafi is a Wahhabi. Nor is either to be equated

with “Islamism”, or political Islam. Today, Wahhabis continue to call

themselves salafis, and to support salafist movements throughout the

world.

Concerning Wahhabism, Master Kayhan said: “In Saudi Arabia, Wahhabis have abandoned the Way of the Prophet (Sunna).

It’s a pity. The Wahhabis are of us, we are not of the Wahhabis.” About

Abdul Wahhab, the founder of Wahhabism, he said: “The British trained

such a man that—they trained him at schools in Arabic knowledge. Now

they [his followers] say to us, ‘You’re infidels, too.’” He once wrote a letter to Saudi officials, who were saying: “We fulfill the Divine Law (sharia)

by performing executions.” In it, he said: “The Divine Law depends on

the Way of the Prophet to a great extent. You have abolished the Way.

How can you base your injustice on the Divine Law that depends on the

Way, which you have abolished?”

One wishes the salafists had been more like the salafis.

“One step beyond what the Prophet of God said is an abyss.

One step behind what the Prophet of God said—that, too, is an abyss.”

The longer version follows.

I

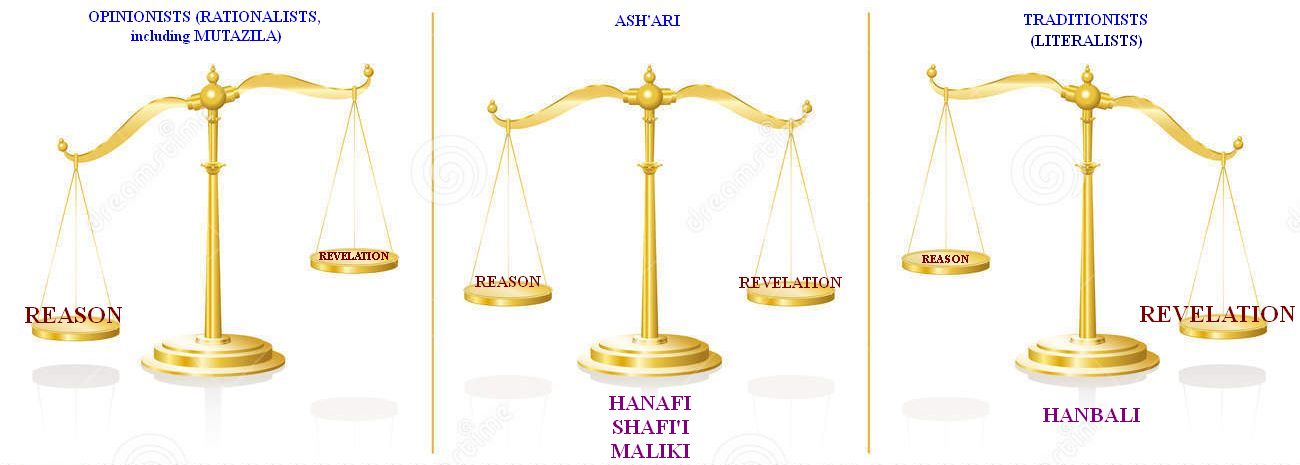

In order to understand what Salafism is, we need to start at a seemingly unrelated point: the relationship between reason (aql) and revelation (naql: literally, what is transmitted).

This relationship and how it is to be resolved occupied an important

place during the early centuries of Islam. In contrast to Tertullian,

who said “I believe because it is absurd,” the Koran always sides with

the intellect: “those possessed of minds” and “do they not reflect” are

oft-repeated phrases exhorting the reader to exercise intelligence.

However, where does Revealed truth end and ratiocination begin?

Reason vs. Revelation

In Islam, revelation comprises two sources: recited revelation (the Koran, wahy matluww) and revelation that is not recited (the Sunna, being the Prophet’s Sayings or Traditions, wahy ghair al-matluww).

By the 9th-10th centuries, there were roughly three factions among the scholars of Islam:

- The rationalists, or the people of personal opinion (ahl al-ray):

These privileged reason over revelation. The philosophers, inspired by

their Greek predecessors, were the ones who went furthest in this

respect. Next came the Mutazilites, who made the Koran subservient to

reason, and on that basis made certain claims that do not concern us

here. Many scholars of systematic theology (kalâm) were also in

this group. Many opinionists found Traditions unreliable and depended

solely on the Koran, which is why they placed more emphasis on reason.

- Opposed to these were the people of Tradition (ahl al-hadith),

who upheld revelation (both the Koran and the Prophet’s Traditions)

above the intellect. They were distinguished by their literalist

approach: that is, they understood Sayings and Koranic Verses literally.

Among these was Ahmad ibn Hanbal (d. 855), the founder of one of the

four schools of Islamic law and a compiler of Traditions. He taught that

everything in the Koran and the Way of the Prophet must be taken

literally and accepted unquestioningly. (Later, Ash'ari also adopted the

latter approach: “God has two hands, without asking how. . . . two

eyes, without asking how. . . . We confess that God has a face.”

However, Ash'ari did not rule out metaphorical or allegorical

interpretations.) Ibn Hanbal’s

biographer Christopher Melchert has stated that he “desired a community

of Muslims, not a Puritan sect considering only themselves believers

(much less a sect perpetually at war with most professing Muslims)” [1a]. (Salafists don’t refer to him much.)

The opposition between rationalists and Traditionists reached such a point that during the reign of the caliph Ma'mun, the Mutazilites, under a period of inquisition (mihna), had Ibn Hanbal arrested, flogged and thrown in jail. (This, of course, still fell far short of the real Inquisition, which had people tortured and burned at the stake. A Saying of the Prophet: “Do not kill any living creature by burning them.”) -

For most Sunnis, the reason/revelation dichotomy was finally resolved

by Abul Hasan Ash'ari (died 936). Ash'ari was originally a Mutazilite.

However, it is related that in his fortieth year (c. 912), he dreamt of

the Prophet three times during the fasting month of Ramadan.

Twice, the Prophet told him to support what was related from himself, namely the Traditions. Disconcerted, Ash'ari abandoned theology and started following Traditions exclusively. However, the Prophet appeared in a third dream on the Night of Power, explaining that he had not told Ash'ari to abandon theology, but only to support the Traditions narrated from him. After this, Ash'ari began to take an intermediate position between the two diametrically opposed schools of thought. A happy mean was thus found between reason and revelation: where revelation was clear and straightforward, it was to be accepted as is, and in matters it did not deal with or where it was ambiguous, reason was to be freely exercised.

The three remaining legal schools of Islam, the Hanafi, Shafi'i and

Maliki, followed the approach of Ash'ari. (Of the four, Hanafi, the

earliest, is also the most tolerant. To be complete, the Shi'ites have

their own law school, called Jâfari, after Jâfar Sadiq, the sixth of the

Twelve Imams.)

The

principle was that reason, by which we discover the truth, cannot be

opposed to revelation, the truth conveyed to us by God and his Prophet.

There can be no logical contradiction between the two. And if there

appeared to be a discrepancy, this would call for further investigation

and subsequent resolution.

(Note that in knowledge pertaining to the Unseen Realm, such as the

existence of spirit, angels and the afterlife, no logical contradiction

is involved. This is simply information belonging to another world

inaccessible to our ordinary physical senses.)

There are four fundamental sources of Islamic law: 1. the Koran, 2. the Way (sunna), 3. binding consensus (ijma) and 4. analogy (qiyas).

Consensus is the agreement of Islamic scholars on a point of Islamic

law. (For the founders of two schools, Abu Hanifa and Ibn Hanbal, only

the consensus of the Prophet’s Companions was acceptable.)

Analogy is extrapolation from what is said in the Koran and the

Traditions to reach a decision for a new, similar situation. As a

fanciful example, suppose that a Tradition were to state that one can

sell a camel for ten dollars. Then it would be appropriate for a person

to sell five camels for fifty dollars. It is noteworthy that although

Ibn Hanbal accepted consensus, he rejected analogical reason, saying

that this would open the door to personal opinion (ray) and hence to subjective conclusions.

The

necessity of consensus and analogy is dictated by reason. If the Koran

and Sunna had been enough by themselves, nobody would have suggested the

use of anything else. Conversely, if consensus and analogy had not been sufficient, further supplements would have been required.

A Pause

We are now about to embark on our voyage into salafism. But before

that, one point needs to be made. During its long history, the world of

Islam was hit by two great tidal waves. The first was the Mongol

invasion in the 13th century. The second was Western colonialism,

starting from the 18th century. While the former was military in nature,

the latter was also economical, social, and cultural, and it hit not

just Islamic lands but the rest of the world (mainly at the hands of the

British, but also the French, Dutch, Belgians, Portuguese...). We will

see salafism emerging as a response to these tidal waves. Whether it was

well-conceived, met its goals, or was co-opted and subverted, is

another matter entirely.

In 1258, Mongol hordes invaded and sacked Baghdad, the seat of the

caliphate. This was to be the first of several such invasions.

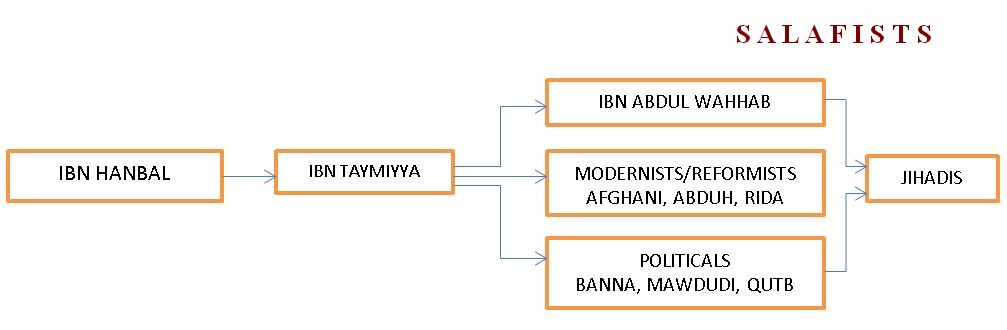

Ibn Taymiyya

Ahmad Ibn Taymiyya (1263-1328) was born in Harran (which is in Urfa in

the southeast of modern-day Turkey). His family was a line of Hanbali

scholars, so naturally he was raised in the Hanbali school of law. When

he was 6 years old, he was forced to flee with his family from Harran to

Damascus to escape another wave of Mongol invasion. He grew up to

become a Hanbali jurist and polemicist with highly untypical views. A

maverick in many ways, he was brought to trial and imprisoned various

times. As might be expected, his views continued to influence the

Hanbalites, while finding little support among the other schools due to

their fringe nature.

Like other Traditionists, Ibn Taymiyya did not believe that logic could

serve as an adequate guide to religious truth, and held that reason

should be subservient to revelation. He endeavored to revive the faith

and practice of Islam by going back to the early Muslim community, the salaf.

He tried to distinguish what he regarded as true Islam from later

innovations in the legal schools, as well as from Shi'ism and Sufism,

fiercely denouncing many sects and cults in the Muslim world as infidels

(kâfir) and apostates (murtadd). (In his later years,

however, he retreated from his earlier position, and towards the end of

his life said: “I do not deem anyone from among the Muslims to be an

unbeliever.” [2])

According to Ibn Hajar Askalani citing Dhahabi, “In discussion he would

be possessed by rage, anger, and hostility against his adversaries,

which implanted enmity in their spirits.” [3]

Ibn

Taymiyya was the first to cast doubt on the four schools. In the words

of Jon Hoover, for him “the views of the school founders are not proofs.

They could be wrong. ... Sunni legal conformism [taqlid] ...

no longer speaks for Islam as a whole.” He did not want to show

disrespect to the founders, and wrote a treatise which he titled Removal of Blame From the Great Imams.

According to Hoover, however, the book is self-serving: in absolving

the founders, the ulterior purpose of Ibn Taymiyya is to free any Moslem

from blame in deriving legal rulings directly from the Koran and

Traditions. “His plea envisions a world in which all jurists, and indeed

all Muslims, are, like himself, subject only to the authority of the

revealed texts and not to the views of other jurists or sclıools.” [3a].

He

used his mastery of dialectical reasoning and polemics to argue against

Ash'ari theology and hence the other legal schools, against Shi'ism,

against Ibn Arabi’s philosophical Sufism, and against other excesses of

some Sufis (such as shrine religion, or practices linked to saints’

tombs and sacred objects). He also held the notorious Satanic verses

incident to be true, the significance of which will become apparent

momentarily. His most notable student was Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya (d.

1350).

As a Hanbali and thus a literalist, Ibn Taymiyya regarded the verses in

the Koran ascribing hands, feet, and location to God as literally true.

This was corporealism (tajsim, jismiyya) and anthropomorphism.

During a sermon he once remarked: “God comes down from heaven to earth,

just as I am coming down now,” and took a step down on the pulpit

staircase. [4]

He was against the monist Sufism of Ibn Arabi and spiritual elitism

among the Sufis. He was not, however, opposed to all forms of Sufism. He

once mentioned the Grand Saint Abdulqader Geylani (Jilani) as “our

shaykh,” and is believed to have been affiliated with the Qadiri order. [5]

We now come to an extremely important point. Ibn Taymiyya actively

supported the empire of his day, the Mamluk Empire in Egypt and Syria,

against further invasions by the Mongols. But there was one problem. The

Mongols were not the Mongols of 1258—in the meantime, they had embraced

Islam. Since all Muslims were brothers by decree of the Koran, it was

forbidden to fight against co-religionists. How, then, were the Mamluks

supposed to protect themselves?

Where there is a will there is a way, and the nimble mind of Ibn

Taymiyya soon found an answer. He said that if a Moslem’s religion was

deficient, he could be opposed and fought against. The Mongols had

accepted Islam, but they were still ruled by the law of Genghis Khan (yasa), not the Divine Law (sharia).

Hence, their religion was defective, so to that extent they could still

be considered (partial) infidels, and it was permissible to fight

against them. To justify this stance, he also gave the examples of the

caliphs Abu Bakr (who fought against tribes that refused to pay

alms-tax) and Ali (who fought the rebel Kharijis for the insincerity of

their religion). [6]

As for the Mongol rule in Baghdad (1258-1335), he adopted an othering

(or otherizing) discourse to discredit their rule. This had never been

done previously, because of the Koranic injunction to “obey those in

authority,” and even Ibn Hanbal, the founder of Ibn Taymiyya’s school,

had declared revolt against a Muslim ruler to be a sin. [7] On the contrary, Ibn Taymiyya claimed that revolt against an infidel or apostate ruler was a religious duty.

This paved the way for what was to come, as we shall see below. Ibn

Taymiyya is important, because practically all salafists draw their

inspiration from him.

Salafist Chart (Simplified).

II

Headings in this section:

Abdul Wahhab

Declaration of faith is enough

Abdul Wahhab’s Thought: An Outline

Friendship and Formality

Two Key Texts

The Satanic Verses

Shirk

Takfir

Wahhabi History

Some Wahhabi Prohibitions

Abdul Wahhab

We shall have to look at Abdul Wahhab’s case in greater detail, due to the ramifications of his approach.

Muhammad ibn Abdul Wahhab (1703-1792) was born in a remote corner of

the Arabian desert called Najd into a family of jurists. His family and

the remaining clerics in Najd all belonged to the smallest of the law

schools: the Hanbali. His father was the leading jurist in town,

dispensing justice and writing legal rulings.

It is said that in his youth, Abdul Wahhab traveled in the Ottoman

lands. (It is a fact that he traveled to Mecca, Medina and Iraq, all of

which were then under Ottoman rule.) He was disgusted by what he saw.

Instead of the austere, secluded Hanbali teaching he was raised on, a

cosmopolitan diversity of other schools, Sufi excesses, and Shi'ism were

to be seen everywhere. The hatred he then conceived for all things

Ottoman was to serve the imperial designs of others (some have

explicitly called him a “British agent”). Feelings of ethnic Arab

supremacy, contrary to the all-embracing message of Islam, also fueled

his hate. Following in the footsteps of Ibn Taymiyya, he branded all

Ottomans as Mongols, against whom jihad was an obligation.

One of the things that aroused Abdul Wahhab’s ire about the Sufis was

the veneration of saints, also called the cult of the saints. People,

and especially Sufis, would visit the graves of saints and petition

their souls for help. This, in Abdul Wahhab’s view, was an abomination:

it was the worst kind of idolatry, setting up others beside God. Showing

them respect was, in his view, worship; asking for their intercession,

unbelief. Yet few other people shared this opinion. Hamid Algar presents

the opposite case:

the

error underlying the Wahhabi identification of all these various

practices as [idolatry or polytheism] is a confusion of means with ends,

a supposition that what is sought from God by means of a person, living or dead, is actually sought from that person, to the exclusion of the divine will, mercy and generosity. [8]

Abdul Wahhab was equally opposed to something as harmless as commemorations of the Prophet’s birthday (mawlid), a much beloved and frequent celebration in Islamic lands.

Abdul Wahhab studied in Medina and Iraq, where he was influenced by the

works of Ibn Taymiyya and his disciple, Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya. He took

their ideas further, fashioning a hostile othering discourse for

Moslems who did not agree with his ideas. The roots of this discourse

lay in his narrow, reductionist conception of God’s Unity (tawhid). [9]

Other Moslems had observed a distinction between faith and good works,

holding that the two were separable. For Abdul Wahhab, true tawhid was

possible only if the definition of faith was expanded to include works

and worship as well. Simply expressing faith with one’s tongue was not

enough: one had to prove it with one’s deeds. This seemingly abstruse

requirement was to have far-reaching consequences.

Hence, Abdul Wahhab considered the declaration of faith (the creed, or

Word of Witnessing) insufficient. This is why those who joined the

Wahhabis were required to pronounce it a second time, as though they

were “born again”. [10]

Needless to say, this runs directly counter to the Way of the Prophet.

Master Kayhan related a well-known Tradition as follows:

Declaration of faith is enough

The

Prophet said, ‘Whoever recites, “There is no god but God and Muhammad

is the Messenger of God” is your brother, don’t draw swords against each

other.’

[During one of the Prophet’s battles,] at the last moment one of the

Qurayshites said: ‘I accept Islam, I accept Muhammad,’ and recited the

declaration of faith. There’s no escape, he’s going to die. He’s also

killed many Muslims himself. His opponent said, ‘You’re lying, you

scoundrel,’ and finished him off. News of this reached the Prophet. He

asks: ‘What did that man say?’ ‘Sir, he recited the declaration of faith

but he was lying, he killed many from our side.’

‘Even if it was a lie, once he pronounced it, you shouldn’t have killed him.’ [11]

On the same occasion, the Prophet declared famously: “Did you open his heart and look inside?”

Abdul Wahhab’s Thought: An Outline

The main tenets of Abdul Wahhab’s thought are as follows: 1.

uncompromising insistence on the absolute unity of God (with which we

have no quarrel), 2. hatred of the Ottoman Empire and everything

therein, 3. diminution of the status of the Prophet to that of a mere

postman, 4. as for all Moslems who did not share his views: first,

calling them idolaters (mushrikun) and apostates (murtadd) and then, branding them as infidels (kâfir) and subsequent excommunication (takfir).

This allowed Wahhabis to rebel and wage war against the Ottomans under

the guise of defending religion: “the struggle with the Ottoman Empire

was framed as a struggle between believers and non-believers.” [12]

“Wahhabism was a pro-Arab nationalistic movement that rejected Turkish

dominance over Arabs under the guise of defending the one true Islam.” [13]

So what did Abdul Wahhab do? He began by restricting the salaf

to the first generation alone: the Companions. This apparently

innocuous move allowed him to exclude not only the first collectors of

Traditions, but the founders of all the law schools. [14]

Of the four sources of deriving legal rulings, he accepted only the

Koran and the Prophet’s Way (partly). He rejected not only scholarly

consensus (which Ibn Taymiyya had also denied) but also analogy (which

Ibn Taymiyya had used extensively, to compensate for his rejection of

consensus views). By this device, Abdul Wahhab was able to repudiate the

four schools, and even to knock half their base out from under them.

This made it impossible for a law school to be formed, because the Koran

and the Way by themselves were not sufficient to make legal rulings.

This is why Wahhabis had to fall back on the Hanbali school—in which

Abdul Wahhab himself had been trained—as default when the social

necessity arose, which was inevitable. Theoretical fancies rarely

survive collisions with the realities of life.

Friendship and Formality

It is not sufficient for Abdul Wahhab to simply be a believer.

A Moslem should befriend Moslems and remain aloof from non-Moslems, that is, be reserved and formal toward them (al-walâ wa-l-barâ, usually translated as “loyalty and disavowal”, from 5:55 and 60:4, respectively). But it is important to maintain balance, to observe a proper sense of proportion, in such matters. This is stated very

clearly in the Koran, which tells Moslems to “deal kindly and justly”

(60:8) with all those who do not show hostility to them because of their

religion. Note that the statement does not contain the word “hate” (as in wa-l-qurhun/bu'dz/nafra).

Even in combat, God has specified: “For the cause of God, fight those

who fight you, but do not go to extremes, for God does not love

transgressors” (2:190).

For Abdul Wahhab, however, this is not enough. One must show active

hostility to those whom he condemns. One must hate—hatred is the basis

of Wahhabism:

it is necessary to hate them, to hate those whom they love, to revile them, and to show enmity to them. [15]

But

love cannot coexist with hate. In mainstream Islam, which Abdul Wahhab

opposes, some words that are misunderstood as “hate” actually mean

“condemn” or “not befriend”, “be reserved toward”. A Tradition states,

“S/he who goes to extremes is ruined.” This is why the Koran calls

Moslems “a balanced, moderate community” (ummatan wasatan,

2:143). If you hate, and worse, if you take hate to extremes—if hate

becomes your obsession—your love of God, too, is consumed in that fire.

Like an acid, hate dissolves love, until nothing is left but that acid

itself. This is where Abdul Wahhab’s conception ultimately ends.

Unbelievable as it may seem, Abdul Wahhab also advocated torture of his

opponents, on the basis of a spurious account about Abu Bakr, the first

caliph, which had been invented by Abu Bakr’s enemies and was already

known to be false. He cherry-picked Islamic history to justify cruel and

inhumane behavior, without any regard to the truth or falsehood of his

“cherries”. [16]

The Prophet said: “You will not (truly) believe until you love one another.” The heart of all religion is love. But some people make hate their religion.

The pure stream of Islamic thought was poisoned by Abdul Wahhab’s hate.

Two Key Texts

Abdul Wahhab left behind two texts, one about God, the other about the Prophet. The first he called The Book of Unification (kitab al-tawhid), the second A Short Biography of the Prophet (mukhtasar sirat al-rasul). The former deals with God in terms of His Incomparability (tanzih),

mainly as a short collection of Traditions (some of them weak or even

spurious). This is important, because the balancing aspect of God’s

Similarity (tashbih) is omitted entirely. Other than that, what

one basically learns from the book is that amulets, talismans,

tomb-veneration, sorcery, and intercession are bad things. [17]

It is the latter work, however, that is highly revealing. There, Abdul Wahhab attempts to cut the Prophet down to size. [18]

No mention is made of extraordinary events surrounding the Prophet’s

childhood or later life which occur in other biographies. On the

contrary, Abdul Wahhab chooses to highlight two events that any enemy of

Islam would champion with glee. One is an ancient fabrication that has

crept into the literature. The other is the famous—or infamous—Satanic

Verses. (See Sidebar 1.)

[Sidebar 1]

The Satanic Verses

I

have not previously written about the Satanic verses (two verses), so

this may be the right place to do so. The event in question happened as

the Chapter of the Star (Sura 53, Najm) was being revealed. The

place was Mecca. As the Prophet was reciting the Verses being

revealed, some Meccan polytheists were also present. A Verse was recited

mentioning three Meccan goddesses, Lât, Manât and Uzza (53:19-20). A

little later, one of the “prostration Verses” in the Koran was recited

at the end of the Chapter (53:62), upon which the Moslems prostrated.

The polytheists also fell down in prostration, because the names of

their goddesses had been mentioned. Thus, everyone present was seen to

prostrate, as per the account in Bukhari (the first of the “Two

Authentic” collections of Traditions). That’s all there is to it. [19]

I

have not previously written about the Satanic verses (two verses), so

this may be the right place to do so. The event in question happened as

the Chapter of the Star (Sura 53, Najm) was being revealed. The

place was Mecca. As the Prophet was reciting the Verses being

revealed, some Meccan polytheists were also present. A Verse was recited

mentioning three Meccan goddesses, Lât, Manât and Uzza (53:19-20). A

little later, one of the “prostration Verses” in the Koran was recited

at the end of the Chapter (53:62), upon which the Moslems prostrated.

The polytheists also fell down in prostration, because the names of

their goddesses had been mentioned. Thus, everyone present was seen to

prostrate, as per the account in Bukhari (the first of the “Two

Authentic” collections of Traditions). That’s all there is to it. [19]

The

biographer of the Prophet, Ibn Hisham, did not mention the Satanic

verses. It fell to Tabarî, a later biographer, to retell the event, but

in a substantially different, apocryphal form. [19a]

According to this, the Prophet, wishing to win over his polytheist

kinsmen, faltered during his recitation, and in that instant Satan

placed the following on his lips:

“These [goddesses] are the exalted cranes (gharâniq) / whose intercession is hoped for.”

Upon which the polytheists supposedly prostrated. Later, God corrected this error and prevented its inclusion in the Koran.

It is impossible to exaggerate the enormity of this claim. Best to let

others say it: “if one verse could be subsequently repudiated as

satanically inspired, why not another—indeed, why not all?” [20] Taken to its logical conclusion, “the entirety of the Qur’an can be seen as ‘satanic’ rather than ‘divine’.” [21]

It doesn’t take great intelligence to see that this line of reasoning

jeopardizes the whole Koran and, by implication, Islam itself.

Naturally, some orientalists (though not all), delighted at having found a straw with which

to beat the Prophet, have had a field day with this account. In Islam,

however, the Traditions of the Prophet take precedence over biographical

material, and this spurious invention cannot be substantiated from

Bukhari, nor from any other of the canonical “Six Books” (Tradition

collections). The Encyclopedia of Islam, the standard reference work, states that “in its present form [the story] is certainly a later, exegetical fabrication” [22], and also: “The story in its present form (as related by al-Tabarî, al-Wakidî, and Ibn Sa'd) cannot be accepted as historical” [23].

Sadly, Abdul Wahhab uses this very fabrication to defame the Prophet.

Whereas, in contradiction to Abdul Wahhab and those whom he either leads

or follows, the same Chapter of the Koran being recited during the

alleged event, said of the Prophet that he “is neither astray nor

misled,” “nor does he speak of his own desire,” “this is nothing other

than Revelation being revealed to him” (53:2-4). That in itself should

have been enough for anyone. As Master Kayhan said: “It would be a

mistake to impute error to the Prophet.” (Or: “It would be wrong to find

fault with the Prophet.”)

With God’s help, the Prophet could sense the Devil coming a mile away. How can anyone even conceive that he could be deceived?

For

some people, the denigration of others is a means of self-exaltation.

The Koran describes such people as “those who have chosen their desires

(their own egos) to be their god” (25:43). It appears as if Abdul

Wahhab’s attempt to diminish the Prophet’s stature is actually nothing

but an effort to exalt Abdul Wahhab.

For

some people, the denigration of others is a means of self-exaltation.

The Koran describes such people as “those who have chosen their desires

(their own egos) to be their god” (25:43). It appears as if Abdul

Wahhab’s attempt to diminish the Prophet’s stature is actually nothing

but an effort to exalt Abdul Wahhab.

Throughout Islamic history, those who have attempted to diminish the

Prophet’s value have had an ulterior motive in mind: to elevate

themselves to his position. This is a two-step project: 1. diminish the

Prophet, 2. set yourself up in his place.

One example of this is the Babai movement in 13th-century Anatolia (not

to be confused with the Bahai). In 1240, Baba Ilyas led a rebellion

against the Seljuki ruler Kayhusrav 2. (It ended badly.) Baba Ilyas

permitted his followers to use the following slogan: “There is no god

but God, Baba is the prophet of God.” This is obviously blasphemy (God

forbid). Such examples are to be found even in our day, though they are

too inconsequential to be written up in history when the time comes.

The Prophet is a human being. Nobody ever said otherwise. But to say

that “he was just a man,” that he is “just a corpse in the grave” (these

things have been said by Wahhabis [23a]),

is deeply disrespectful. Out of all humanity, only specific persons

were chosen by God as prophets, and out of these, only one was chosen as

the final prophet. Surely such a person cannot be equated with any

ordinary man you might happen to pull off the streets.

To attach to the Prophet the importance which is his due is not to

worship the Prophet. There is deep error in this. It is through him that

we learn about God. To trivialize the Messenger is to trivialize the

Message, and by implication, to trivialize the One who sent the message.

Wars have broken out, or been resumed, from the mistreatment accorded

to envoys. And once you declare war on God, there is no way you can win.

![I bear witness that there is no god but God, and that Mohammed is His Prophet. If you love God, follow [His Prophet], then God will love you, and forgive you your sins (3:31).](http://www.geocities.ws/henrybayman/en/godprophet2.jpg)

If you de-emphasize the Prophet, what is distinctively Islamic is lost. Jews, Christians, even Deists agree

with the first part of the creed: "There is no god but God." The more you reduce the Prophet, the closer you approach Deists.

(Alice: "Is this why Moslem youth are turning to Deism?" Bob: "Deprived of a human role model, what else can they do?")

Shirk

Abdul Wahhab declares the love of anything other than God to be shirk. Often translated as idolatry, polytheism or associationism, shirk finds its best explanation in the first of the Ten Commandments: “You shall have no other gods before (beside) Me.”

Abdul Wahhab radically misunderstands shirk;

he has his categories seriously confused. This leads him to believe

that ancient polytheists were monotheists at heart, but called upon

intermediaries; “otherwise those mushrikun bore witness that

God alone is the creator, without any partner”. On the other hand, all

Moslems who do not accept his views have been polytheists for hundreds

of years. The verses from the Koran that he presents as evidence pertain

to actual monotheists, such as Jews, Christians, and followers of the

Patriarch Abraham (hanifs), or to novice converts in the Prophet’s time, whose understanding of the religion had not yet matured.

Now observe: “the ancients did not, in times of prosperity, assign

partners to God nor did they call on angels, sacred personages (al-awliya'), and idols. As for times of hardship, they directed their petitionary prayer exclusively to God.”

But this is an exact definition of monotheism. So Abdul Wahhab thinks that the polytheists were actually monotheists.

Again: “the ancients used to call upon persons close to God, prophets,

friends of God, or angels, or direct their petitionary prayers to trees

and rocks, objects obedient to God, not rebellious against Him. As for

the people of our time, they call upon the most sinful of men together

with God.” Hence, “the shirk of earlier generations was slighter than that of the people of our age” (All quotations here are from his Kashf al-Shubuhat [24]).

This last is a different way of expressing Ibn Taymiyya’s earlier view:

“It is a well-established rule of Islamic Law that the punishment of an

apostate will be heavier than the punishment of someone who has never

been a Muslim”. [25]

If polytheism equals monotheism, then it is an easy jump, perhaps, to

“monotheism equals polytheism”. Which would be amusing in itself, were

it not for the fact that its consequences have been so disastrous.

According to Abdul Wahhab, even if a believer refrained from shirk

and did everything in accordance with correct Islamic teachings, he

could still be considered an apostate if he committed the sin of loving

anyone or anything as much as—or more than—God.

Next, based on Verse 9:31, he accuses anyone who follows any of the legal schools of shirk, indicting the entire tradition of jurisprudence (fiqh), which includes his own school, the Hanbali:

jurisprudence (fiqh), which is what God has called shirk and the taking of scholars as lords.[26]

In his writings, Abdul Wahhab frequently demonizes jurists as “devils” or “the spawn of Satan” [27]—invective that recalls Martin Luther’s railings against the Pope as the “unspeakable Antichrist at Rome”.

There is one small problem, however. By the same token, would not any

follower of Abdul Wahhab himself be equally taking him for lord, and

thus be guilty of shirk? Worse, what about a follower of the

Companions? And worst of all, would not any follower of the Prophet also

be guilty of the same? (He does seem to make an exception for the

Prophet—but on what grounds?) What Abdul Wahhab says renders Islam

itself impossible. His illogical definition of shirk ends in nothing short of nihilism. [28]

Between adherence to himself and excommunication, Abdul Wahhab leaves

no place for sin (although he claims to do so, thus contradicting

himself), for repentance, for the forgiveness of God, for His attributes

of Compassion and Mercy, which preface almost every Chapter of the

Koran.

It was his clearly flawed notions that led almost all his

contemporaries to position themselves against Abdul Wahhab, including

his own father, and his own brother Sulayman who wrote a tract

criticizing Abdul Wahhab. In it, he made it clear that in Abdul Wahhab’s

view, the only criterion for being a Moslem (and thus safe from

reprisals) was to blindly follow Abdul Wahhab and obey him unthinkingly.

[29]

Takfir

The most important point, however, where Abdul Wahhab and his followers

diverged from Ibn Taymiyya, was that they sanctioned the use of force

against their own co-religionists. Anyone who did not agree with Abdul

Wahhab was declared a polytheist (mushrik), infidel (kâfir) or apostate (murtadd).

Since this meant the vast majority of the world’s Moslems, they could

all be killed. Here we must remember that the Prophet himself refrained

from killing Jews and Christians under his jurisdiction, even if they

disagreed with him, and that mainstream Islam (Sunnism), following the

Prophet’s example, has always been tolerant even of other faiths.

Although takfir

is translated as “excommunication”, it has implications that go beyond

what is ordinarily understood by excommunication in the West: exclusion

from Communion, shunning, shaming, banishment, and expulsion of an

individual from a community. By takfir, however, a person’s very life, property, and family are rendered forfeit. It is obligatory to kill them (wâjib-ul-qatl), it is allowed to shed their blood and seize their property (halâl al-dam wal-mal),

and their wives and daughters can be violated and enslaved. From this,

it may be inferred that there is much profit to be gained by takfir-ing

someone, and some people obviously did. According to the Prophet, one

who initiates something new, whether good or bad, will have a share in

the proceeds of all who come after him. Abdul Wahhab will continue to

accrue the bitter fruit of the trail he pioneered until the end of time.

For Abdul Wahhab, any act by a Moslem that he considers to be shirk expels that person automatically from the religion. His ideology of takfir

is not limited to abstract scholarly debate, but is the engine behind

the political and military movement he initiated, as we shall see below.

After his alliance with the House of Saud in 1744, Abdul Wahhab’s

vocabulary increasingly turns to fighting and killing (qital) in connection with takfir. In his view, the Moslems of his time are worse than the mushrikun of the Prophet’s age. [30]

(Because Wahhabis thought that Moslems were worse than idolaters and

people of other religions, they chose alliances with the latter as the

lesser of two evils. The history of Wahhabism is the history of moving

close to non-Moslem nations and away from Moslems—the exact opposite of

what al-walâ wa-l-barâ called for.)

Abdul Wahhab then takes this one step further: he posits takfir by association. It is obligatory to excommunicate not only those guilty of shirk, but also all those who hesitate or fail to excommunicate the guilty ones. His takfir spreads like contagion: failure to excommunicate shirk is itself grounds for excommunication. “Whoever does not excommunicate them (the mushrikun), he is by that an unbeliever.”

For the case of Europe in the Middle Ages, this used to be called a

witch hunt. And yet, this too is grounded in Ibn Taymiyya, who used a

similar approach in judging the Shi'ites. [31] In all this, significant parallels exist between Abdul Wahhab and the Kharijite sect (the Khawarij) of the 7th century, as has been noted by critics ever since.

After Abdul Wahhab’s death, his grandson, Sulayman Ibn Abdullah

(1785-1818), laid out the practical and theological guidelines not only

for excommunicating Shias and Sufis, but also for branding all

non-Wahhabi Sunnis as apostates. Shias are regarded as polytheist

infidels who are not Muslims because of their love for Ali and the

Twelve Imams. Sulayman expanded the circle of kufr to include all Muslims except the Wahhabis. [32]

Now the accusation of unbelief (kufr)

is a very delicate matter, the consequences of which, if untrue, are

very grave. For the Prophet has said: “If a person calls his brother an

unbeliever but it is not true, then it [his accusation] rebounds on him”

[33].

So one has to be very careful in making such allegations. Mawdudi,

himself a salafist, has observed: “As to the question of a person being

in fact a believer or not, it is not the task of any human being to

decide it. This matter is directly to do with God, and it is He Who

shall decide it on the Day of Judgment. [Takfir] is in fact to oppose God Himself” [34].

Wahhabi History

Abstract ideas have concrete results in real life.

In 1744, Abdul Wahhab took refuge in a village called Dariya (or

Diriya), ruled by the local clan of Saud and its chieftain, Muhammad ibn

Saud. Abdul Wahhab soon ingratiated himself with his new hosts, and

their alliance was consolidated by marriage. In 1747, they established a

crude form of government. The power-sharing arrangement between Abdul

Wahhab and Saud was that the clan would supply the military and

political rulers, while Abdul Wahhab, his family, and his descendants

would constitute the religious authority. This proved to be the

beginning of a mutually fruitful and long-lasting collaboration, which

still survives after almost three centuries. The resulting Saudi state

had boundless territorial ambitions [35], and everywhere they went, Saudi forces (themselves Wahhabis) would be accompanied and egged on by Wahhabi preachers.

From the start, the Wahhabi ideology of takfir

served the Saudi clan well in their project of expansion, conquest, and

plunder. Abdul Wahhab and his troops waged dozens of battles in the

region of the holy cities, Mecca and Medina. They destroyed the shrine

at the Prophet’s birthplace and the tomb of his first wife Khadija. The

Prophet’s tomb itself was pillaged and its treasures distributed as “war

booty” among Saudi soldiers. Wahhabi forces committed horrendous

massacres everywhere in Arabia. [36]

Abdul Wahhab burned many books, arguing that the Koran was enough for humankind (on this, see “quraniyyun” below). He ordered his men to dig up and scatter the graves of Moslem saints or turn them into latrines. [37]

The house of Khadija, in particular, was turned into public toilets.

The graves of the Prophet’s Companions at the Baqi cemetery (called the

“Garden of the Eternal”) were desecrated, their tombs leveled to the

ground, and their identities erased.

In 1787, Abdul Wahhab declared himself the leader of all Moslems worldwide, and ordered jihad

against the Ottomans. The next year, the Saudis and British military

forces working together occupied Kuwait, wresting it from Ottoman

control. [38]

Twice before, in 1755 and again in 1775, the British had tried but

failed to take Kuwait from the Ottomans. With Wahhabi help, they

succeeded on their third attempt.

For nearly two hundred years, from 1757 to 1947, the British ruled in

India. In order to protect their colonial interests there, the British

would in time establish outposts everywhere in the vast crescent of land

mass surrounding the Indian Ocean, ranging from South Africa to

Australia, and including Arabia as a nearby springboard. This meant

the invasion of formerly Ottoman territories. In this they were helped

by the Saudi-Wahhabi alliance: “in reality Wahhabis were incited and

supported by English colonialists to rebel against the Ottomans” [39].

Remarkably, Wahhabi violence was never directed against the aggressive

non-Moslem empire—their fury was aimed solely at the Ottomans. Britain

encouraged the Wahhabis, with an eye to the endgame: the eventual

collapse and dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire.

The Wahhabis killed thousands of Shi'ites and Sunnis in their invasions

of Karbalâ and Ta'if, plundering the Shia holy site of Karbalâ in Iraq

and soon extending their rule over the entire peninsula. In the 20th

century, at least 10 thousand were killed or wounded (amputated) [40]

so that the third and last Saudi state could be established. With the

discovery of its vast oil reserves in 1938, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

became a major player in the world’s economy, politics, and geopolitics.

Following the oil crisis of 1973, the immense wealth accumulated by the

kingdom was used to spread Wahhabi proselytism all over the planet.

Rather than correcting the error of their ways, they are determined to

convert all the world to Wahhabism, ostensibly in the name of

“salafism”.

In 1924-5, Wahhabi fanatics tried to destroy the Prophet’s tomb (which

is in the Prophet’s Mosque in Medina). Only the uproar from the world’s

Moslems prevented them from doing so. In 2014, authorities in charge of

the Mosque were still discussing moving his grave to an undisclosed

location in the Baqi cemetery, thus resulting in its destruction. [41]

It appears that this final insult waiting to be hurled at the Prophet

is still an ongoing project with the Wahhabis. Only its utility as a

cash source, worth billions annually, would prevent the Kaaba from

suffering the same fate.

Some Wahhabi Prohibitions

- According to Abdul Wahhab, if a Moslem says that eating bread or meat is unlawful, then s/he has become an infidel.

- Art and nonreligious poetry are equal to associating partners with God.

- Abdul Wahhab and his followers despised music, banning traditional as well as other kinds of music in the belief that they led to sin.

- Wahhabis forbade the use of honorific words, such as “master,” “doctor,” “mister,” or “sir.” Using them is to associate partners with God.

- Participating in festivities, vacations, or other social events (such as birthday and New Year celebrations) invented by non-Moslems is enough to make you an infidel.

- Abdul Wahhab condemned minarets and tombstones because neither were in use during the first years of Islam. (Minarets were therefore demolished everywhere, and when the two holy cities fell into the hands of his followers, the tombs of saints were razed to the ground.)

- It is not permitted to glorify buildings and historical sites. Such action would lead to shirk because people might think those places have spiritual value. (Think of the Kaaba.)

- If a sick person were healed and he were to say, “this medicine benefited me,” that person would be guilty of shirk.

- If someone said “such-and-such a saint aided me when I appealed to him as an intermediary,” ditto.

- It is forbidden for children to fly kites.

- Taking photos with cats is forbidden (2016).

- So are visits to hot springs, forests, mountains, or caves for spiritual or physical health.

- Finding pleasure in sorcery is prohibited.

- Female drivers are infidels who deserve to die.

- For men, shaving off beards, wearing silk or gold are forbidden.

- As are smoking, playing backgammon, chess, or cards, or failing to observe strict rules of sex segregation.

III

The Impact of the West

With Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt in 1798, the era of colonialism in

Islamic lands began in earnest. This confronted Moslems with a

predicament that was harder to resolve than the Mongol invasions. The

impact of the Mongols had mainly been military; that of the West was to

be, in addition, social, economic, political, cultural, educational,

technological...

Faced with an existential crisis of monumental proportions, Moslems

living in the invaded and colonised lands were dumbfounded at first. How

had this happened? How had the successes of Islam been reversed to

become defeats? A scapegoat was sought and, before long, found:

something must have gone wrong with the religion itself. Certainly the

Prophet and the Devout Forerunners could not be faulted: Moslems shrank

from imputing blame to them, for this would be tantamount to sacrilege.

In that case, then, it was the later captains of the ship of Islam who

had to be at fault. They had strayed from the Straight Path that would

have assured success. What had to be done was to return to the Golden

Age of Islam, those halcyon days of the Prophet and the first three

generations. Later generations must have misunderstood and

misinterpreted the religion. It was necessary to eliminate the

methodologies developed in order to better comprehend revelation, to

bypass the middlemen, and to face the scriptures directly. Everything

that came afterwards had been undesirable accretions that slowly changed

the course of the ship and weighed it down until it foundered.

Therefore, the reasoning ran, if these later encumbrances were ditched,

Moslems could rise again from their benighted condition and regain their

former glory. What was required was a merciless purge of all later

acquisitions.

What generally escapes notice is that the Moslem reaction was

formulated under duress, in already colonized countries. That stress

distorted the outcome and deflected it from what it might have been

under less stressful conditions. It came about as a defensive reaction

rather than a natural, healthy process of growth.

Colonial rule began to force modernization on the Moslem world in the

19th century. The Moslem response took two forms, one traditionalist and

the other progressive. The Wahhabis had already been experimenting with

the conservative approach. By the end of the 19th century, however, the

superiority of the West’s technology, science, and cultural

achievements had become undeniable. According to some, a return to a

historical—perhaps even mythical—Golden Age was out of the question. The

time had come for Islam to be updated, to become modernized, and the

only way to do this was to emulate the West.

The Modernist Reformers: Afghani–Abduh–Rida

Jamaluddin Afghani

(1839-1897) was the teacher of Muhammad Abduh (1849-1905), who was in

turn the teacher of Rashid Rida (1865-1935). Together, this trio defined

the modernist-reformist agenda within Islam between the 1870s and

1930s. Their emphasis on rationalism was closer to the Mutazila than to

salafism, but they were nearer to it in other respects. It is noteworthy

that Afghani and Abduh never called themselves salafis, and only Rida

began to use the term in his later years.

Afghani was not only a modernizer, but also an anti-colonialist and

political activist. He thus fathered both modernist Islamic movements

and Islamism. He believed that Islamic lands simply had to throw off the

yoke of Western colonialism.

Here are some excerpts from Afghani’s 1883 polemic with Ernest Renan:

All religions are intolerant, each one in its [own] way. . . Muslim

society has not yet freed itself from the tutelage of religion. . . I

cannot keep from hoping that Mohammadan society will succeed in breaking

its bonds and marching resolutely in the path of civilization someday

after the manner of Western society. . . the Muslim religion has tried

to stifle science and stop its progress. It has thus succeeded in

halting the philosophical or intellectual movement and in turning minds

from the search for scientific truth. . .

It is permissible, however, to ask oneself why Arab civilization, after

having thrown such a live light on the world, suddenly became

extinguished; why this torch has not been relit since; and why the Arab

world still remains buried in profound darkness.

Here the responsibility of the Muslim religion appears complete. It is

clear that wherever it became established, this religion tried to stifle

the sciences and it was marvelously served in its designs by despotism.

. . Religions, by whatever names they are called, all resemble each

other. No agreement and no reconciliation are possible between these

religions and philosophy. Religion imposes on man its faith and its

belief, whereas philosophy frees him of it totally or in part. . . So

long as humanity exists, the struggle will not cease between dogma and

free investigation, between religion and philosophy. . . [42]

Afghani

was fond of such Islamic philosophers as Ibn Sina and Nasruddin Tusi.

He gave lessons on Ibn Khaldun’s Muqaddima (“Introduction”), which is a

philosophy of history and considered the founding text of sociology. His

adherence to reason exceeded that of the Mutazila. Toward his later

years, Afghani came to believe that the Islamic world needed a

Reformation like that of Europe, with himself as the new Luther [43]—a project that never found fruition.

Afghani accused Moslems of three failings—and he was right. But these had already been spelled out in the Koran.

- For his first diagnosis, laziness, the Koran prescribed: “A person can have nothing but what s/he has labored for.” (The equivalent of the Biblical “He who does not work, neither shall he eat” (2 Thess. 3:10).)

- For his second, stupidity: “Deaf, dumb, and blind, they cannot understand.” (2:171) (In explaining the stupidity of disbelievers.)

- For the third, ignorance: “One who knows and one who does not know—how can they be the same?” (39:9)

Meaning: get out of those spaces, don’t be like that. If there has been

failure, it does not belong to Islam but to those Moslems who have

neglected to follow it. If Moslems don’t heed their own Book, how can

they expect to succeed?

Like Afghani, Muhammad Abduh

was influenced by progressive Western thought, and was also convinced

that Islam is compatible with reason. If the apparent sense of a passage

contains what seems to be a contradiction, he said, “reason must

believe that the apparent sense was not intended.” [44]

The believer is then free to interpret the sources in such a way as to

resolve the contradiction. Similarly, he believed the Koran and science

to be compatible. Genies (the jinnî) are conceived of as inter-

or extradimensional sentient beings (what Castaneda/don Juan called

“inorganic beings”); his identification of genies with microbes was

likely a gesture to the positivism of his age.

Abduh aimed to reform Islam by returning it to its original state. He

espoused various views that ran counter to those of Ash'ari and the

rulings of the four schools. He believed that the social ills of the

East were caused by “beliefs and opinions introduced into Islam by

different groups like the Sufis and others”, which “wrought harmful

results. The reformation will extract these beliefs from the nation. It

will replace them with authentic Islamic beliefs” [45].

Three famous Orientalists (Goldziher, Schacht and Massignon),

independently of each other, characterized Afghani’s and Abduh’s thought

as cultural Wahhabism. [46]

Both Abduh’s and Rashid Rida’s

teachings were influenced by Ibn Taymiyya and his students, such as Ibn

Qayyim al-Jawziyya and Ibn Kathir. Advocating a “return to the

sources”, Rida explicitly condemned adherence to any of the four law

schools (lâ madhhabiyya), an attitude that both his mentors are also suspected of having shared. [47]

Like his predecessors, Rida actively strove for the modernization of

Islam, even creating a school for which he prepared a special

curriculum. Rida opened his Institute of Knowledge and Guidance (Dâr al-ilm wa-l-irshad)

in Cairo, Egypt, in 1912 as a reformist Islamic school. This project

was short-lived, however, being brought to a premature end by the onset

of World War I.

Rida had hoped to enlist political backing from a powerful Islamic

nation for his endeavors, initially pinning his hopes on the Ottoman

caliphate. But then, something cataclysmic happened: the Ottoman Empire

ceased to exist, followed by the abolition of the caliphate in 1924.

It was then that Rida transferred his allegiance to the Saudi Wahhabis.

This is also roughly the time when he first began to use the term

“salafi”. In Arabia, King Saud was in the process of forming a new Saudi

state. Thereafter, Rida would be seen to side with the Wahhabis. [48] Thus, although the modernist reformers had not consciously started out as Wahhabis, they ended up joining forces with them.

The Politicals: Banna–Mawdudi–Qutb

While this article is not specifically intended to deal with political

Islam, it has become customary to mention it when dealing with salafism,

so a few words may be in order.

Whereas the modernists had attempted to bring Islam into conformity

with modernity, the Islamists aimed at bringing all social institutions,

and especially the state, into conformity with Islam. The former

attempted to reform Islam, the latter believed that what needed change

was not Islam, but everything else. In doing so, however, they redefined

Islam as a version that was uniquely theirs, incorporating concepts

borrowed from western political thought.

Initially, the anti-colonial movements in Islamic lands were directed

toward the foreign occupiers. But as independence was won and new

national governments came to power, the newcomers inherited many

governance structures instituted by the colonial powers without change.

Soon, it became clear that post-colonial states were continuing to

implement many of the secular and/or problematic policies and programs

of their predecessors.

It was at this point that political Islam, or Islamism as it has been

called, arose. The idea was that an Islamic state, governed by the sharia, would resolve all the problems that had stubbornly persisted. Political activism was necessary to bring about this outcome.

Hassan (al-)Banna

(1906-1949) took his inspiration from the modernist school. He became

an eager student of the Islamic reformists Abduh and Rashid Rida.

Banna was a dedicated follower of Rida. He recast Islam not as a

religion but as an ideology. There was a need, in his view, for

re-Islamization of life in Egypt in all fields infected by Western

influence. [49]

Calling for Islamization of the state, the economy, and society, Banna founded the Society of the Muslim Brotherhood (Ikhwan al-Muslimun) in 1928. Like Rida, the Brotherhood (Ikhwan

or MB for short) repudiated the four legal schools. It believed that

the schools had been divisive, and aimed to unite Moslems by

transcending them. Especially in its earlier period prior to 1970, it

claimed to follow the “original” Divine Law (sharia) of the Prophet before it became divided into schools. [50]

The fact is that the schools were founded in order to elucidate the sharia,

to unpack what was already contained in the Verses and Sayings in

implicit form. To understand this, we may refer to an example taken from

mathematics. (See Sidebar 2.)

[Sidebar 2]

Euclidean and Non-Euclidean Geometries

Briefly, Euclid based his geometry on certain axioms and four

postulates. However, these postulates, by themselves, were not enough to

do geometry with. Something extra was needed. Euclid settled upon a

fifth and final postulate, which was rephrased by mathematician John

Playfair as:

- Through any given point, exactly one straight line can be drawn parallel to a given line.

Now there was something different about this fifth postulate. It was not intuitively obvious, but neither could it be reduced to the first four. As a matter of fact, other alternatives were also possible. These gave rise to what are known as non-Euclidean geometries:

Through any given point, more than one straight line can be drawn parallel to a given line.

Through any given point, more than one straight line can be drawn parallel to a given line.

In the 19th century, Riemann developed spherical geometry (positive curvature) based on this.- Through any given point, no straight line can be drawn parallel to a given line.

In the same century, hyperbolic geometry (negative curvature) was developed by Lobachevsky on this basis.

As you can see, changing just one postulate can lead to quite different geometries, all of them equally valid.

Now the point of all this is that in developing a legal code, your

axioms and postulates can lead to different results, just as different

initial conditions will lead a dynamical system to evolve in different

ways. The outcome will change based on your methodology and points of

emphasis. The astounding thing is that the founders of the legal schools

were so rigorous in their methodology that only four were the result,

instead of a profusion of schools. They diverge in various minute

details, but by and large they overlap. Nor are they as different from

one another as geometries of differing curvatures. And the founders were

all deeply respectful of each other, recognizing that the alternative

derivations were also valid ones, given their frameworks.

Obviously, then, there was no Islamic law (fiqh) in the time of the Prophet: it had not been codified yet.

One final point: if you eliminate the fifth postulate in order to go

back to the “original” postulates, you are left with no geometry at all.

In India, Abul Alâ Mawdudi

(1903-1979) took the Egyptian Banna’s position one step further. He

developed a systematic vision of political Islam. His originality lay in

combining Islamic tradition with Western philosophical and political

thought. Banna and Mawdudi were both gradualists: both believed in

peaceful jihad (struggle) through setting an example and social activism.

Islam, Mawdudi declared, “is a revolutionary ideology.” He was

borrowing terms from Marx in an age when Marxism was in vogue. The Koran

was a “socioreligious institution” [51]. Mawdudi founded a party: the Islamic Community (Jamaat-e-Islami),

in 1941. Equating Islam with the state, he called for making Pakistan,

and even all of India, an Islamic state based on the Divine Law. He also

criticized the famous Ghazali for defending Sufism. Here are some

quotations from Mawdudi:

‘Jihad’ refers to that revolutionary struggle and utmost exertion which the Islamic Party brings into play to achieve this objective.

Islam wishes to destroy all states and governments anywhere on the face

of the earth which are opposed to the ideology and programme of Islam

regardless of the country or the Nation which rules it. The purpose of

Islam is to set up a state on the basis of its own ideology and

programme... [52]

According

to Mawdudi’s program (not Islam’s), a small vanguard of Moslems were to

take over the state and impose piety on society.

Sayyid Qutb

(1906-1966) was a leader of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt and a

contemporary of Mawdudi. Like all fundamentalist ideology, Qutb’s

thought was in no way traditional. On the contrary, it was unmistakably

modern, incorporating elements from western philosophers such as

Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, and Heidegger. [53]

For Qutb, too, Islam was “an all-embracing and total revolution” [54]. In 1902, Lenin had published a book, What Is To Be Done,

in which he formulated the concept of a vanguard that would lead the

proletariat to revolution and thence to power. The Bolshevik Party was

to be that vanguard during the Russian Revolution. First Mawdudi and

then (with greater emphasis) Qutb adopted this notion of a vanguard,

recasting it in Islamic terms. Although they did not agree with Marx or

Lenin, both found some of their concepts useful. It appears that Qutb,

like Mawdudi, wished to promote his version of Islam as an alternative

to communism—intentionally or not, they appropriated some of its

terminology.

According to his last book, Milestones (also known as Signposts on the Road), Qutb believed that Moslems are not followers of “true Islam”, which “has been extinct for a few centuries” [55]. Instead, they are living in Jahiliyya, (the Age of) Ignorance. This left Moslems once again open to takfir,

a pratice we have already seen in Abdul Wahhab, because those who call

themselves Moslems are not actually Moslem—except, of course, for Qutb’s

vanguard, a group of Moslems modeling themselves after the Companions

of the Prophet.

Where Banna was pragmatic, Qutb was a radical [56].

In their defense, it may be said of Mawdudi and Qutb that neither of

them advocated violence. (Qutb said force was to be used only as a last

resort.) [57] Those who came after them would not be so scrupulous.

In 1979, political Islam was given an additional impetus by Khomeini’s

“Islamic revolution” in Iran. This, in turn, kickstarted a Wahhabi

response that took the form of an unending worldwide propaganda

campaign.

* * *

Today,

salafism is considered to be composed of three groups. (There are other

classifications as well.) These are the purists, the politicals, and

the jihadis [57a].

The purist or quietist salafists do not concern themselves with

politics, and want to be left alone to live and spread their religion in

peace. The politically engaged salafists want to promote salafism by

active involvement in political affairs. And jihadist salafists,

considering that political involvement is not enough, expect to achieve

their goals by violent means. Al-Qaeda and ISIS/IS belong to this latter

group. When a certain Egyptian Qutbist teamed up with a Saudi Wahhabi,

the fuse leading to the 21st century was lit.

And that is where this historical survey ends.

Time for Some Assessments

It is all very well and praiseworthy to return to the path of the Pious

Ancestors. At first glance, there is nothing objectionable about it.

But returning to the roots should not, must not, entail throwing the

baby out with the bathwater. For consider where this might lead:

Salafists are so fixated on the literal reading of revelation that they

dispense with 1400 years of commentaries on Islamic Law, not to mention

theology, literature, and philosophy. The repudiation of the three legal

schools ends by repudiating the fourth one as well, leading to the

emergence of “non-schoolists” (lâ madhhabiyya)—which, as we

have seen, can be traced back to Abdul Wahhab himself, and indeed to Ibn

Taymiyya. This has already happened among some salafists such as

Shawkânî and Albânî, who claim that the Hanbali school is a later

invention, just like all the others. [58] The concept of befriending Moslems and distancing or reserved conduct toward non-Moslems (al-walâ wa-l-barâ)

has also led them to oppose present-day Wahhabis, because the latter

are allied with the Saudi state, which in turn is in bed with Western

powers. Thus, in an irony of history, the concepts of Abdul Wahhab have

boomeranged back on his flock. Despite all this, however, non-schoolists

seem to get along quite well with Wahhabis and Hanbalites, even allying

themselves with them in some places, perhaps because of the maxim that

birds of a feather stick together.

The non-schoolists (or anti-schoolists) believe that anyone is qualified to derive judgments from the proof-texts. We have already seen that this was also the goal of Ibn Taymiyya. This is the same as saying that everyone not only can be, but actually is,

a lawyer, a doctor, or an engineer, professions that require years, if

not decades, of education. Any amateur is expected to be able to do

their job. As Fadl has observed:

According to Salafism, effectively anyone was considered qualified to return to the original sources and speak for God. The very logic and premise of Salafism was that any commoner or layperson could read the Qur'an and the books containing the traditions of the Prophet and his Companions and then issue legal judgments. Taken to the extreme, this meant that each individual Muslim could fabricate his own version of Islamic law. [59]

Or, as Thomas Paine put it: “My own mind is my own church.”

If everybody has their own law, this means there is no law at all.

Now: Sunni Islam is the four schools, so this lies beyond the scope of “the people of the Prophet’s Way and Community” (Ahlus Sunna wal Jamaah).

Hence, although salafism and Wahhabism have emerged in Sunni

geographies and their adherents continue to call themselves Sunni, they

are movements outside Sunni Islam, and so are best described as

non-Sunni sects. They are not alone in this: there have been many sects

and cults in history that have deviated from the Sunni path. But then,

Shi'ism is similarly repudiated. And so is Sufism, the esoteric, inward

aspect of Islam. They are therefore also anti-Shi'ite and anti-Sufi. The

intricacies of juristic reasoning, the subtleties of Sufism, the

edifice of theology are all discarded. What, then, remains of the

religion? Only what one can salvage with one’s own vastly inferior and

narrow acumen.

Next we have the “Koran alone”ists (quraniyyun),

who claim that the Traditions are unreliable and attempt to interpret

the Koran using their reason. This will naturally lead to the

uncontrolled proliferation of intellectual opinions, each opposed to

every other. If interpretations of the Koranic Verses are needed, who

better to supply them than the one closest to the Source? Master Kayhan

said, “Nobody can interpret the Quran according to their own lights” [60].

He also said: “Both the Holy Verses and the Sayings (Traditions) came

from his lips. With Traditions, he reinforces Verses. With Traditions,

he brings examples to Verses.” And further: “One step beyond what the

Prophet of God said is an abyss. One step behind what the Prophet of God

said—that, too, is an abyss” [61]. Which, of course, is the real reason for past and present calamities.

Now, every religion worth its salt is composed of two parts: the

exoteric, dealing with external, outward beliefs and practices, and the

esoteric, which deals with the inner life and spirituality. The latter

is the role of Sufism in Islam. Where a religion lacks one of these, it

has had to be found or invented.

For example, the Kabbalah was instituted in the 13th century as a

complement for legalistic Judaism. In Christianity, an interest in

alchemy, Freemasonry and Rosicrucianism flourished to supplement the

dry, rationalistic discourse of Protestantism. In pre-communist China,

people professed three religions at once: Confucianism dealt with

external matters and ethics, Taoism with the inner world and the

esoteric, and Buddhism was adopted as a sort of bridge between the two.

The combination of Taoism and Buddhism produced Ch'an Buddhism (known as

Zen in Japan).

Hence, human beings need both the outward (zâhir) and the inward (bâtin) aspects of religion. And so do Moslems.

When

you take an axe to a full-grown tree, you cannot hope to grow another

one in its place barring the efforts of thousands of highly skilled

scholars toiling away for many centuries. A building that has taken

years of vast effort to build can be demolished in minutes if not

seconds. It is much easier to destroy than to build. But then, why try

to grow a new tree if you have one already?

When

you take an axe to a full-grown tree, you cannot hope to grow another

one in its place barring the efforts of thousands of highly skilled

scholars toiling away for many centuries. A building that has taken

years of vast effort to build can be demolished in minutes if not

seconds. It is much easier to destroy than to build. But then, why try

to grow a new tree if you have one already?

Secondly, you do not know if you will be able to reach a consensus with

others. For everyone has an opinion, and every mind works differently

from every other. Once reason alone is the guide, you cannot prevent the

runaway proliferation of viewpoints. And hence, it will be impossible

to rebuild the structure or regrow the tree. Once glass is broken, the

process is irreversible. Remember, the nail that Luther drove into the

door of the Wittenberg church shattered Christianity into thousands of

pieces. Half a millennium has passed, and it has not yet recovered from

that blow.

Salafism as the Protestantization of Islam

In this context, Western observers throughout history were not far

wrong in labeling Wahhabism, and later salafism more generally, as

“Islamic Protestantism”. As some most recent examples, Jonathan Brown, a

scholar of Traditions (hadith), has said: “Salafism is like Protestantism”. [62]

Bryan S. Turner, a sociologist of the postmodern age, equates

“Islamization” (Islamist-ization) with “political radicalism plus

cultural anti-modernism”, thus implying Islamists and the politicization

of Islam. On this basis, he says: “Islamization is a political movement

to combat Westernization using the methods of Western culture, namely a

form of Protestantism within Islam itself.” [63]

The Downsizing of Islam

Where have all these efforts ended?

In their struggle to accomodate modernity, Moslems have lost contact

with their history, and come up with a modern Islam that is very

different from the traditional forms of Islam that came before it. In

taking this step, they have abandoned interpretive engagement with all

earlier Islamic disciplines (philosophy, literature, mysticism, Islamic

science, theology, study of the Koran, study of Traditions, art, music,