—If the doors of perception were cleansed, every thing would appear to man as it is, infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things through narrow chinks of his cavern.

William Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

—To be awake is everything.

Gustav Meyrink, The Green Face

Who was Ahmet Kayhan, my Master?

We shall discover the answer at the end of this text.

In what follows, we shall attempt to unpack the meaning of some sayings belonging to Mohammed, the Prophet of God.

1. The Prophet said: “This world is the prison of the faithful.”

2. The Prophet said: “People are asleep, they wake up when they die.”

Right now, as you are reading this, you imagine you are awake. No! You are asleep, and dreaming.

3.The Prophet said: “Die before you die.”

We can infer, then, that the Prophet is telling us to WAKE UP before we die.

The Koran says: “God wishes to purify you completely,” “to lead you out of darkness into light.” (33:33, 33:43)

(Sleep is traditionally associated with darkness, consciousness with light. There are various levels of consciousness, and the light of the midday sun, as psychologist Carl Gustav Jung also noted, stands for superconsciousness.)

And: “God is the Light of the heavens and the earth… Light upon light.” (24:35)

Now, what does the Prophet mean when he says that “this world is a prison”? The first and trivial meaning, of course, is that the faithful will go to Heaven in the next world, compared to which this world is indeed a prison.

But is that all?

In order to shed light on this question, we turn to Plato’s famous story, the Allegory of the Cave (henceforth referred to simply as “the Cave”).

The Sufis held Plato in the highest regard, referring to him as “the divine Plato.” They even claimed that the Prophet Mohammed said: “The divine Plato was a prophet, but his people didn’t know it.”[1] We are about to find out why they did so.

What Dostoevsky’s account of the Grand Inquisitor in The Brothers Karamazov is for literature, that Plato’s account of the Cave in The Republic is for philosophy. The 20th-century philosopher and mathematician, Alfred North Whitehead, once observed that the whole of western philosophy in the last 2500 years “consists of a series of footnotes to Plato.” And in like manner, we would not be far wrong if we said that the entire philosophy of Plato consists of a series of footnotes to the Cave. So the Cave is that important.

As everyone knows, Plato learned what he knew from his teacher Socrates, whom Plato always writes about. Of course, it is not obvious what precisely is Plato’s gloss and what genuinely belongs to Socrates, but we won’t let that little twaddle stand in our way.

As the dialog seems a bit outdated, what follows is a fanciful conversation as it might occur today. The clay animation below gives some idea of what Plato is talking about. The original version of the allegory is reproduced in an Appendix.

Plato’s Cave Today

Plato and Socrates were observing Earth from their vantage point in the Great Beyond.

“You know,” said Socrates, “now that humanity has reached the twenty-first century, I think your allegory of the Cave needs an upgrade to a newer version.”

“Pardon me, Master,” said Plato, “but wasn’t the allegory originally yours?”

“So many centuries have passed that memory fails me,” mused Socrates. “Besides, people call it by your name. But I’ve been thinking about this, and I’ve come up with something viable, I believe. Listen up and see how you like it.

“There’s this psychologist who decides to perform a long-term study on perception management. Accordingly, his university leases a small movie theater, or maybe they allocate an auditorium for the project, and a bunch of orphans are recruited as subjects for the experiment.”

“I don’t know,” said Plato. “They have laws against child experimentation nowadays.”

“The university arranges permission somehow,” snapped Socrates. “anyway, don’t interrupt me so I can tell the whole story to the end.”

“In the theater,” he went on, “the subjects are strapped to rows of comfortable seats in an auditorium. Behind this large chamber is the projection room. From here, a movie is projected with a movie projector onto a large projection screen at the front of the seats. I’m sure you’re familiar with the mechanism?”

“A powerful arc light projects images on celluloid film streaming in front of it onto the screen.”

“Exactly. Caterers attend to the needs of subjects during intermissions. At least two decades pass, during which the subjects are constantly exposed to movies during their waking hours. That reminds me, aren’t children exposed to TV for about the same period these days?

“Now, the psychologist is interested in the long-term effects of perceptual distortion. Of course he could, through displaying proper movies to his subjects, give them a pretty good idea of what is going on in the outside world. But because of his chosen field, everything the subjects watch is out of whack. They are mostly shown shadows of objects instead of the objects themselves, or weird abstract surreal designs, and hear only reverberating echoes instead of direct sounds. And so the years pass. In time, the subjects lose all recollection of the outside world.”

“That’s a strange image, and those are strange subjects,” said Plato, “though I can see the parallels with your earlier Cave allegory.”

“They’re not much different from us, you’ll see,” replied Socrates. “Having no other experiences, the subjects try to form a consensus reality from their perceptions. To them, the truth would be literally nothing but the shadows, abstract images and echoes.”

“Obviously.”

“Finally, the day comes for the psychologist to release a subject. He leads her out of the auditorum’s entrance into the foyer. What will happen? When the subject emerges from the auditorium door, and looks towards the light, she will suffer sharp pains. The glare will distress her, and she will be unable to see the realities themselves while, in her former state, she had seen only their shadows. Then, if the psychologist tells her that what she saw before was an illusion, but that now, when she is approaching nearer to being and her eye is turned towards more real existence, she has a clearer vision, what will be her reply? And you may further imagine that the psychologist is pointing to the objects as they pass and requiring her to name them, won’t she be perplexed? Won’t she fancy that the shadows she formerly saw were more real than the objects that she is now shown?”

“Definitely,” concurred Plato.

“And if she is compelled to look straight at the light, won’t she have pain in her eyes which will make her cringe and turn away? She will refuse to gaze at the objects of vision which she can see. The shadows she was accustomed to, she will conceive to be in reality clearer than the things which are now being shown her.”

“Absolutely.”

“Next, she is reluctantly dragged out into the street, and held fast until she's forced into the presence of the sun itself. Won’t she likely be pained and irritated? When she approaches the light, her eyes will be dazzled, and she will not be able to see anything at all of what we now call realities.”

“Not immediately, anyway.”

“First she will need to get used to the sight of the world outside. At first, she will see the shadows best. Next, the reflections of men and other objects in the water, and then the objects themselves. Then she will gaze upon the light of the moon, the stars, and the starry sky. At first, she will see the sky and the stars by night better than the sun or the sunlight by day.”

“Precisely.”

“She will be able to look at the sun last of all, and not merely at reflections of it in the water. Then she will see the sun in its own proper place, and will contemplate it as it is.”

“Certainly.”

“She will then understand that it is the sun which produces the seasons and the years. That it is the benefactor of everything in the visible world, and in one way or another, the root cause of all things which she and her friends have been accustomed to behold.”

“Clearly, she would first see the sun and then reason things through.”

“And when she remembers her previous condition, and what passes for wisdom in the cinema and her fellow subjects, don’t you think she would count herself lucky to be out of there, and would pity those she left behind?”

“Certainly, she would.”

“And supposing they had got into the habit of ranking each other on those who were quickest to observe the fleeting shadows and images, to remark which of them went before, which followed after, and which were together, and who were therefore best able to predict what comes next. Do you think that she would care for such honors and glories, or envy those who won first prize? Wouldn’t she consider it better to be free even though poor in the outside world, rather than return to the measly prizes of that dark theater?”

“Yes, I think she would suffer anything rather than return to those false notions and live that miserable life.”

“Next, the psychologist returns our subject to her previous condition. Wouldn’t her eyes be full of darkness at first?”

“Of course.”

“And suppose there were a contest, and she had to compete in measuring the shadows with the subjects who had never been taken outside, while her sight was still weak, and before her eyes had become steady―and the time which would be needed to acquire this new habit of sight might be considerable. Wouldn’t she seem ridiculous? Her companions would say of her that out she went and in she came, minus her eyes. That it was better not even to think of going out. And if one of them tried to free another and lead him out to the light, let them only catch the offender, and they would put him to death.”

Plato wiped a tear from his eye. “What’s the matter?” said Socrates. “Master,” said Plato, “that is precisely what they did to you! You were tried, convicted, and sentenced to death, for supposedly ‘corrupting’ the youth of Athens. What I call enlightenment, they called corruption!”

“Now, now, my son,” replied Socrates, “it’s all in the distant past. I remember how distressed you were as I drank the poison hemlock, but even then you were more disturbed than I was. We have to face the vicissitudes of life with equanimity. We all had to die someday, and we did. Death spares no one.

“Anyway, let me finish my allegory update. The movie theater is our observable world or the world of the senses, the arc light is the sun, and the journey outside is the ascent of the soul in the spiritual world. The idea of God is apprehended last of all. As our good friend Plotinus pointed out after you came over to this side, the sun in the parable symbolizes God. His light is seen only with an effort, and when seen, He is also understood to be the Universal Author of all things beautiful and right; indeed, of all things. God is the source of light and of the sun in this visible world. He is the immediate source of reason and truth. And this is the power upon which whoever would act rationally, either in public or private life, must have his eye fixed.”[2]

The Sufi version

As it happens, there is also a Sufi version of the Cave:

A woman was sentenced to life imprisonment as the result of a crime she committed. The woman, who was pregnant, gave birth to a baby in her cell when her term was full. We shall call the child Evan, for reasons to be explained below. Because she had no relatives outside, she raised the child in her cell. The child reached the age of fifteen without any knowledge of the external world.

One day, a wise man was branded as a thought criminal and placed in the same jail. When he met Evan, he thought to himself: “God must have sent me here for Evan’s sake.” The sage began teaching the child. Since Evan was very intelligent and clever, they made quick progress. The more Evan’s knowledge grew, the more the questions did as well. For his part, the sage was very happy about these questions. Evan was quick at learning, digesting, and wanting to see the truth.

Evan’s mother, however, was not happy. If Evan ever learned the whole truth, she might lose her only child. So she was opposed to the sage teaching Evan. But the sage wanted to deliver the child from this cloistered existence which, he thought, Evan had not done aything to deserve.

When Evan had learned enough, the sage said: “I have one last lesson to teach you. But I leave it up to you to fulfill its requirements. The choice will be yours.” The child said, “I’ll do what I can.”

“In that case, follow me,” said the sage. He took the child to the jail’s main exit and showed Evan the external world. Up to that moment, the sage had given abstract knowledge and shown some pictures. But now, Evan was observing the outside world in person, and beholding the beauties contained therein. The child asked: “I don’t know why I’m here. Can I leave?”

The wise man said: “You can leave this place and gain your freedom, which is your birthright, whenever you want. There is no reason for you to stay here.”

Evan was overjoyed, but then the child’s eyes clouded over: “What about my mother?”

“Your journey with her ends here,” said the sage. “From now on, you should live your life freely. But if you want to be liberated from this prison, you should be prepared for combat.”

Evan asked: “Sir, I have no enemies. Whom shall I fight against?” The sage replied: “Against your own self. You must leave behind everything that obstructs your freedom. This isn’t easy. Even if you leave it, it won’t let go of you, just like your mother. Winning freedom is possible only with a strong will, patience, and constant struggle. This is called a war without a peace. It doesn’t end till the goal is reached.”

Evan looked one last time at the cold walls of the jail, mourned all those long years of imprisonment, and resolved, no matter how much Mother would beg, to start a new life on the outside.

We have imprisoned ourselves with our own consciousness, and locked the door to our cell with our own hands.[3]

That’s the story. Now, we have called the child Evan for two reasons. First, this name can be given to both boys and girls, and hence is gender-free. Second, the meaning of Evan in Celtic is “young warrior.” In the original Sufi story, the child is called Mujahid, which also means “warrior, struggler.” Considering the young age of the child, Evan seemed a fitting choice.

Asleep in a Cave

Once the story of the Cave is told, Socrates/Plato goes on to explain his ideas of justice and the form of the good. The Cave siginifies much more than that, however. For it is first and foremost a tale of spiritual education, even more than an intellectual one. It describes the soul’s ascent in the spiritual world, finally perceiving that all things owe their existence to the “sun,” which, as Plotinus well realized, symbolizes God, whom both he and Plato called "the One" (Gk. to En, Ar. al-Ahad). As such, the provenance of the Cave would appear to be Ancient Egypt, where both Socrates and Plato are claimed to have spent many years. Plato himself said he respected the wisdom of the Egyptian priests. The Prophet’s Ascent (meeraj) is the archetype for all spiritual ascents of this kind.

We can easily see that the Cave, associated with philo-sophia or “the love of wisdom,” has relevance for religion, spirituality, and mysticism as well.[4] Although philosophy was originally part and parcel of this whole package, starting with Plato’s student Aristotle, it became a separate specialized discipline. We have to go back to Plato and the pre-Socratics to recover the roots of philosophy, which, being “a series of footnotes,” it is never wholly divorced from.

On the second quotation from the Prophet, “People are asleep, they wake up when they die,” the following excerpt from Gustav Meyrink’s The Green Face sheds light. Here, waking up is equivalent to emerging from the Cave:

Man is firmly convinced that he is awake; in reality he is caught in a net of sleep and dreams which he has unconsciously woven himself. The tighter the net, the heavier he sleeps. Those who are trapped in its meshes are the sleepers who walk through life…indifferent and without a thought in their heads. Seen through the meshes, the world appears to the dreamers like a piece of lattice-work: they only see misleading apertures, act accordingly, and are unaware that what they see are simply the debris of an enormous whole. These dreamers are not, as you may perhaps think, dwellers in a world of fantasy and poets. They are the everyday men, the workers, the restless ones, consumed by a mad desire for restlessness. [In the end, all their efforts come to naught.] They say they are awake, but what they think life is, is really only a dream, every detail of which is fixed in advance and independent of their free will.

There have been, and still are, a few men who have known that they were dreaming.[5]

“Who dies once, does not die again”[6]

Finally, we come to the third saying attributed to the Prophet, “Die before you die.” As Plato points out, perfect knowledge of the Real is impossible in this life, so philosophy is a preparation for dying and being dead.[7] What happens when you do this? Examples are so scarce that it is hard to generalize. But for the Sufis, it means going through a death-rebirth experience where you are reborn in a way radically different from your earlier constitution.

In his Mystery of Mysteries, the Grand Sheikh Abdulqader Geylani, one of the greatest Sufis, draws attention to the words of Jesus: “Unless a man is born again, he cannot enter the Kingdom of God” (John 3:3). “What is meant by this,” says the Grand Sheikh, “is birth in the world of meaning, the spiritual world.” Geylani also sheds light on another saying of Jesus: “Unless one is born of water and of the Spirit, he cannot enter the Kingdom of God” (John 3:5). He says that the first birth, from water, refers to birth into the physical world. This follows directly from the Koranic verse: “We have formed man of mixed water” (76:2). The second (spiritual) birth, he says, makes a human being “twice-born”: “Birds, too, are twice-born. In its first birth, the bird consists of an egg. If it is not reborn, leaving its shell behind, it can never fly.” And the same applies to human beings.

In the 1999 underground cult movie, The Matrix, Neo (played by Keanu Reeves) dies and is resurrected with a Sleeping-Beauty kiss by Trinity. After that, he can fly, freeze bullets in mid-air, and do various astounding things.

Many have already remarked the obvious parallels between The Matrix and Plato’s Cave.[8] The Virtual Reality world Neo inhabits before he resurrects is a “dream world,” “a prison for your mind” as his mentor Morpheus calls it, and is very similar to Plato’s Cave. Once he awakens, he can see the reality of the Matrix as a computer program, as streams of digits instead of the images it conjures. His vision has penetrated to the underlying reality.

And to the Sufis, a deeper (or higher) reality is what it’s all about. Because The Matrix incorporates Gnostic elements, the real world Neo wakes up to is a “desert of the real.” An evil Artificial Intelligence keeps humanity in chains, dreaming in the virtual world, while it sucks off the life energies of humans. The Gnostics used to think that God, who is good, could not have created human suffering, so there had to be a lesser, demonic demiurge who acted as Creator god. Both Gnostics and The Matrix are pessimistic in this respect. But for the Sufis, the world—or worlds—one wakes up to, can only be superior to the present one. The Sufis are an optimistic lot. When we are purified completely, we emerge from darkness into light, not into a deeper darkness.

Ahmet Kayhan

And if you want the answer to that perilous question: “Who was Ahmet Kayhan?” He was one who helped all of those who were lucky enough to come into his presence to perceive a Cave (or a Matrix)—to the extent of their abilities—in an era when such a traditional perception seemed to have been buried with the ancients. And he did this with humility, wisdom, and unselfish love.

APPENDIX: PLATO’S CAVE

Our story begins one fine day in the agora (town square). Socrates is talking to Glaucon, Plato’s brother:

Socrates: And now, let me show in a parable how far our nature is enlightened or unenlightened: Imagine human beings living in a cave, which has an opening towards the light and reaching all along the den; here they have been from their childhood, and have their legs and necks chained so that they cannot move, and can only see before them, being prevented by the chains from turning round their heads. Above and behind them a fire is blazing at a distance, and between the fire and the prisoners there is a raised way; and you will see, if you look, a low wall built along the way, like the screen which marionette players have in front of them, over which they show the puppets.

Glaucon: I see.

S: And do you see men passing along the wall carrying all sorts of vessels, and statues and figures of animals made of wood and stone and various materials, which appear over the wall? Some of them are talking, others silent.

G: You have shown me a strange image, and they are strange prisoners.

Like ourselves; and they see only their own shadows, or the shadows of one another, which the fire throws on the opposite wall of the cave?

True; how could they see anything but the shadows if they were never allowed to move their heads?

And of the objects which are being carried in like manner, they would only see the shadows?

Yes.

And if they were able to converse with one another, would they not suppose that they were naming what was actually before them?

Very true.

And suppose further that the prison had an echo which came from the other side, would they not be sure to fancy when one of the passers-by spoke that the voice which they heard came from the passing shadow?

No question.

To them the truth would be literally nothing but the shadows of the images.

That is certain.

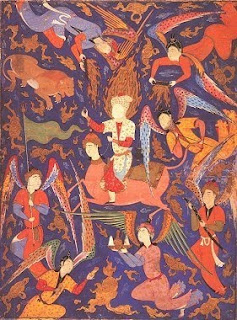

(It is a bit difficult to grasp the physical environment Socrates is describing. The following illustration will provide better insight about the setting of the Cave.)

Socrates: And now look again, and see what will naturally follow if the prisoners are released and disabused of their error. At first, when any of them is liberated and compelled suddenly to stand up and turn his neck round and walk and look towards the light, he will suffer sharp pains; the glare will distress him, and he will be unable to see the realities of which in his former state he had seen the shadows; and then conceive some one saying to him, that what he saw before was an illusion, but that now, when he is approaching nearer to being and his eye is turned towards more real existence, he has a clearer vision, -what will be his reply? And you may further imagine that his instructor is pointing to the objects as they pass and requiring him to name them, -will he not be perplexed? Will he not fancy that the shadows which he formerly saw are truer than the objects which are now shown to him?

Far truer.

And if he is compelled to look straight at the light, will he not have a pain in his eyes which will make him turn away to take and take in the objects of vision which he can see, and which he will conceive to be in reality clearer than the things which are now being shown to him?

True.

And suppose once more, that he is reluctantly dragged up a steep and rugged ascent, and held fast until he's forced into the presence of the sun himself, is he not likely to be pained and irritated? When he approaches the light his eyes will be dazzled, and he will not be able to see anything at all of what are now called realities.

Not all in a moment.

He will require to grow accustomed to the sight of the upper world. And first he will see the shadows best, next the reflections of men and other objects in the water, and then the objects themselves; then he will gaze upon the light of the moon and the stars and the spangled heaven; and he will see the sky and the stars by night better than the sun or the light of the sun by day.

Certainly.

Last of all he will be able to see the sun, and not mere reflections of him in the water, but he will see him in his own proper place, and not in another; and he will contemplate him as he is.

Certainly.

He will then proceed to argue that this is he who gives the season and the years, and is the guardian of all that is in the visible world, and in a certain way the cause of all things which he and his fellows have been accustomed to behold.

Clearly, he would first see the sun and then reason about him.

And when he remembered his old habitation, and the wisdom of the den and his fellow-prisoners, do you not suppose that he would count himself lucky on the change, and pity them?

Certainly, he would.

And if they were in the habit of conferring honours among themselves on those who were quickest to observe the passing shadows and to remark which of them went before, and which followed after, and which were together; and who were therefore best able to draw conclusions as to the future, do you think that he would care for such honours and glories, or envy the possessors of them? Would he not say with Homer, “Better to be the poor servant of a poor master, and to endure anything, rather than think as they do and live after their manner”?

Yes, I think that he would rather suffer anything than entertain these false notions and live in this miserable manner.

Imagine once more such a one coming suddenly out of the sun to be replaced in his old situation; would he not be certain to have his eyes full of darkness?

To be sure.

And if there were a contest, and he had to compete in measuring the shadows with the prisoners who had never moved out of the den, while his sight was still weak, and before his eyes had become steady (and the time which would be needed to acquire this new habit of sight might be very considerable) would he not seem ridiculous? Men would say of him that up he went and down he came without his eyes; and that it was better not even to think of ascending; and if any one tried to free another and lead him up to the light, let them only catch the offender, and they would put him to death.

No question.

(And indeed, the story proves prophetic, for Socrates is tried, sentenced to death and poisoned with hemlock in the end for trying to enlighten the city’s youth.)

This entire allegory, you may now append, dear Glaucon, to the previous argument; the prison-house is the world of sight, the light of the fire is the sun, and you will not misapprehend me if you interpret the journey upwards to be the ascent of the soul into the intellectual world according to my poor belief, which at your desire I have expressed, whether rightly or wrongly God knows. But, whether true or false, my opinion is that in the world of knowledge the idea of good appears last of all, and is seen only with an effort; and, when seen, is also inferred to be the universal author of all things beautiful and right, parent of light and of the lord of light in this visible world, and the immediate source of reason and truth in the intellectual; and that this is the power upon which he who would act rationally, either in public or private life, must have his eye fixed.[9]

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] Kane Eflatuni ilahi Nebiyyen velakin cehile kavmehu (Turkish transliteration), Niyazi Misri, Hizriya-yi Cedida. Conversely, Nietzsche described Mohammed as an Arab Plato (Ian Almond, The New Orientalists, London: I. B. Tauris, 2007, p. 201).

[2] With apologies to Plato, Socrates, and all their fans. Adapted from Plato, The Republic, Book VII, 514a-521b, http://www.sacred-texts.com/cla/plato/rep/rep0700.htm.

[3] http://www.yazete.com/Kurtulus-yolu_43709.html

[4] “…mystical theology, or perhaps better, a doctrine of contemplation, is not simply an element in Plato's philosophy, but something that penetrates and informs his whole understanding of the world." Andrew Louth, Origins of the Christian Mystical Tradition, New York: Oxford University Press, 1981, p. 1. Louth refers to “the religious dimension of Plato’s thought” on p. 2.

[5] Quoted at http://www.freespeechproject.com/green.html.

[6] Saying of the Prophet.

[7] Phaedo, 64A, in Louth, loc. cit.

[8] Notably: -John Partridge, "Plato's cave and the Matrix," in Christopher Grau (ed.), Philosophers Explore The Matrix, New York: Oxford U. Press, 2005, pp. 239-257.

-William Irwin, "Computers, Caves, and Oracles: Neo and Socrates," in William Irwin (ed.), The Matrix and Philosophy: welcome to the Desert of the Real, Peru, Ill: Carus Publishing, 2002, pp. 5-15.

-Lou Marinoff, "The Matrix and Plato's Cave: Why the Sequels Failed," in William Irwin (ed.), More Matrix and Philosophy, Chicago, Ill: Open Court, 2005, pp. 3-11.

[9] Plato, The Republic, Book VII, 514a-521b, from http://www.sacred-texts.com/cla/plato/rep/rep0700.htm.