A scene from Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom (2018).

Say: “If you love God, follow me, so that God will love you and forgive your sins.”

—God, to the Prophet (3:31)

I leave you two things. You will never stray as long as you follow them:

the Book of God and the Way of His Prophet.

—The Prophet of God

(Hakim, Mustadrak, vol. 1, p. 93; Imam Malik, Muwatta, 1601.)

(Hakim, Mustadrak, vol. 1, p. 93; Imam Malik, Muwatta, 1601.)

The movie version of Michael Crichton’s science-fiction novel, Jurassic Park (1990), and its sequels continue to bear fruit for the movie industry and interested viewers alike. The most recent one, the fifth in the series, is Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom

(2018), in which humans try to rescue dinosaurs from a dying volcanic

island. The main theme is a genetic engineering experiment gone horribly

wrong: a cautionary tale about a theme park of cloned dinosaurs that

(always!) ends in disaster. Advanced computer graphics utilize pixel-level control to bring alive, on the big screen, creatures that have been extinct for some sixty million years.

Crichton’s second novel on the subject, called The Lost World (1995), was adapted (as was the first) by Steven Spielberg into a film by the same name in 1997. Before Crichton’s Lost World, however, there was another: the original (one and only!) The Lost World (1912) by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. This has also been repeatedly adapted to the cinema.

The

plot differs from Crichton’s novels. Led by the formidable George

Edward Challenger, a professor with an assyrian beard and an ego the

size of Texas, a band of explorers sets off for South America in search

of undiscovered country. There they discover the eponymous “lost world,”

which has been preserved, as if in amber, from the ravages of time.

They encounter dinosaurs, ape-men, and even human beings. Unfortunately,

there is no escape from the lofty perch on which they are now marooned.

Conan

Doyle drew the inspiration for his novel from Mount Roraima in

Venezuela: a flat summit with an altitude of almost 3 kilometers,

surrounded on all sides by 400-meter-high cliffs.

Finally,

a young man whose life they had saved comes to their rescue. He gives

the journalist (the narrator) a bark of wood, on which the following

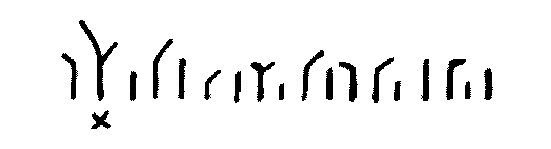

figures have been inscribed:

The

group quickly figures out that the drawing is a map of the caves on the

hillside above them, and that “x” marks the one cave that leads through

to the outer world. Thus, they are able to return to their home and to

civilization.

I

now submit that the “lost world” is actually an allegory for our own

world. Here are wonders and dangers galore. Here we can encounter human

beings, ape-men, and yes, even monsters. Our world is “lost” in the

sense of being a “fallen kingdom.”

We are all lost sheep, immersed in a world of matter—divorced, so we

think, from all higher realities, including the spiritual world.

“We

have come from God, and we shall return to Him” (2:156). But the really

worthy thing is to do this while we are still alive. “The true calling

of man,” said Aldous Huxley, “is to find the way to himself.” This does

not mean that Alice, for instance, should find the way to “Alice,” but

that Alice should find her way to the “divine spark” within every human,

the innermost core of their being, wherein resides God, for God is

present everywhere—including the center of our Hearts. This is the

“journey to the Homeland” (safar dar watan) that the Sufi masters speak of.

Religions

provide us with a means, a trek through a cave, by which we can find

our way back to God, to Ultimate or Unconditioned Reality. Just as only

one cave led the travelers out of the Lost World, only one religion (or

religious philosophy) provides us today with the means to escape the

labyrinth, though all aspire to do so.

I

spent years studying many philosophies and many religions before I

discovered the “cave” marked with an “x”. To cut a long story short,

that turned out to be the Mohammedan Path. Master Kayhan said: “A step beyond what the Prophet of God said, that’s an abyss. A step short of it: that, too, is an abyss.” (Here,

“Mohammedan” is not meant in the same sense that “Christian” means for

Christians—it does not ascribe divinity to the Prophet, even if he was

worthy of such praise.)

Now

what does this entail? The first requirement is impeccable ethical

conduct. Without that, no amount of worship will get you very far.

Illicit Gain (stealing, embezzling and so on) is out, of course. And—this

may come as a surprise to some—Illicit Lust (extramarital sex with any

other than a spouse of the opposite gender) is also banned. (Marital

sex, on the other hand, is fully encouraged.) These two points are the most important of all.

Second, the distinctive characteristic of Ahmet Kayhan’s—and hence the Prophet’s—path was that it combined the

exoteric and the esoteric, morality and mysticism, the Divine Law and

Sufism: the inner dimension in addition to the external one. Sufism

stands to the Divine Law as spirit does to body: the one without the

other is either a ghost or a corpse—in any case, not a living, breathing

entity. As Imam Malik, founder of one of the four schools of

jurisprudence in Islam, observed:

“He

who practices Sufism without learning Sacred Law corrupts his faith,

while he who learns Sacred Law without practicing Sufism corrupts

himself. Only he who combines the two proves true.” (Quoted by H.A. Hellyer.)

For

some years, I have been trying to communicate Master Kayhan’s teachings

to the world in a contemporary idiom, preserving its essence. Like the

young fellow in The Lost World, I now hand the piece of bark to you.